For the last few weeks, as so many of us were isolated in dorm rooms and apartments, unable to see people face to face, or hug each other, opening our windows for sunlight, checking our temperatures twice a day, praying together through closed doors in this unexpectedly austere Lenten season, a friend and fellow seminarian began to create a space – online – for prayer and meditation. Every weekday afternoon, he sets on a sunny table next to a window a couple icons, incense and recorded music – beautiful, ancient chant – and turns on Facebook Live. For half an hour, we can open our laptops or our phones and sit and watch the sunlight, study the faces of Mary and Jesus, listen to music and, for a little while, be at peace, despite our anxiety and uncertainty as this pandemic spreads around us in the world outside.

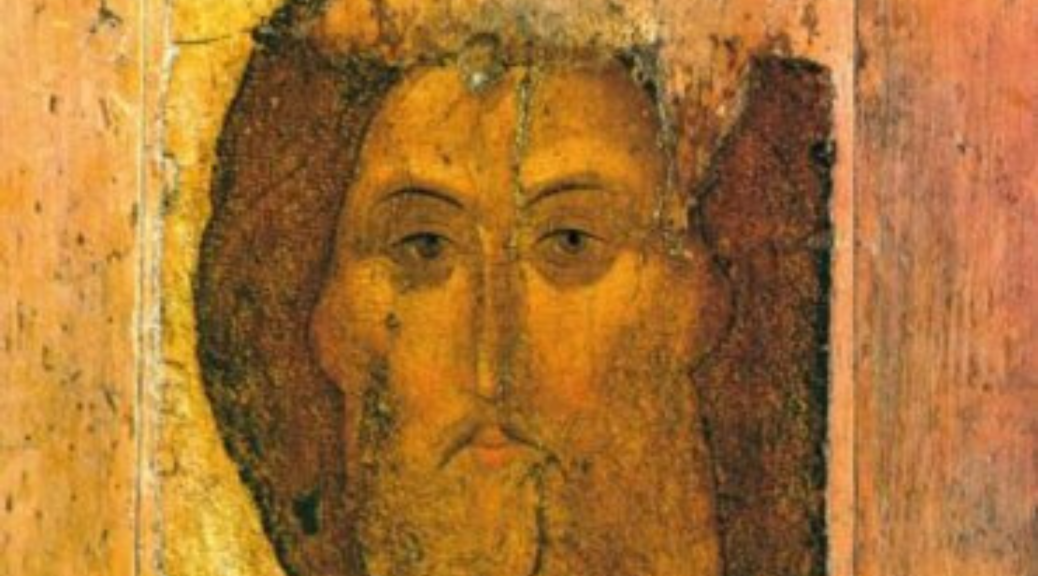

One of the icons he chose is this image, the Savior of Zvenigorod. The original icon was created around 600 years ago in Russia, one of a number of icons made for a church, most of which have been lost over centuries of conflict and struggle. This particular icon was discovered in 1918, around the end of the First World War, by accident, in a barn, when a man turned over a plank in some steps. The face of Jesus gazes at us as it did him, framed by the damage of time and war and the elements, lost and then found again. It is compassionate and somewhat sad, and still beautiful despite the scratches, the cracks, the fading of colors, the brokenness of the wood and paint and years around his eyes.

This morning, we begin Holy Week by telling the story that is to come. It is a story that upends expectations – this morning, a king who arrives in Jerusalem on a donkey. On Thursday, a teacher who washes his apostles’ feet. On Friday, a Messiah who fails, who refuses to defend himself and dies, humiliated and in agony, on a cross. In between, friends who betray, who fall asleep, who turn away; crowds that shout for the blood of the innocent.

It is a story of brokenness, of cracks and faded colors, of goodbyes, of thorns and tears and earthquakes. It is the story of what no one expected, of events that left Jesus’ disciples, friends and loved ones, in grief and fear, not knowing what would come next, scattered, without hope or light.

We know something of that right now, in this long Lent. We know what has been promised – every year we celebrate resurrection with brightly colored eggs and daffodils and children in Easter dresses and joyous music. This year, we cannot celebrate that resurrection in our church, and it feels as if that resurrection may not come, as we stay in our homes, waving through the windows, worrying over coughs and headaches, missing our routines and our communities, afraid we may lose jobs or health or friends or loved ones.

We’ve heard this Passion story many times over the years. It is a frightening story, violent, all the way to the end: “the earth shook, and the rocks were split,” the tombs were opened. In the Gospel of Mark, darkness falls on the land; in Luke, the sun is extinguished. And the curtain of the Temple, the holiest of holies, is torn in two.

I’ve always read that tearing of the curtain as part of the devastation – another treasured, solid thing that is destroyed along with Christ. What I didn’t realize, and what Jesus’ apostles at the time couldn’t know, is that the tearing of the curtain was the hope in the brokenness – it was the beauty of the eyes of Christ, gazing from a cracked and forgotten piece of wood. For centuries, the curtain in the Temple – and the curtain in the tabernacle in the wilderness, before that – was what hid God from God’s people – protected the people from the fire of God. The only person who ever walked behind that curtain was the high priest, giving sacrifices to God to atone for the sins of God’s people. The Temple was what we might call a thin place today – a place, the place, where divinity and mortality, heaven and earth met.

The tearing of the curtain wasn’t a sign of an ending, but of a beginning. It marked the moment when there was no long anything dividing us from our Creator. In the life of Jesus, God walked with us, wept with us, healed and talked and prayed and laughed with us. He was a difficult child and a rebellious adult; he preached and traveled and shared meals with humanity. He was afraid, and in pain, and in sorrow, and died, because he loved us. The tearing of the curtain is the face of Christ, compassionate, sad, beautiful, looking at us from the broken wood of the cross. The tearing of the curtain is the completion of Immanuel, God with us.

The tearing of the curtain tells us that even in violence and uncertainty, even in earthly destruction, God’s promise and God’s love are present. Even in our isolation, even when we feel alone and afraid and abandoned, we are not. And because Christ journeyed with us, we take this journey with him over the coming week. We live through his last days and hours with him, and we know that there is sunlight on the other side. There will be Easter eggs and daffodils again. We are not alone. Church is not bounded by the walls and roof of a building – God is not bounded by the curtain of God’s Temple, or a cross, or a tomb. We walk through this darkness together, and we will live and be loved on the other side of it.

This reflection was written and recorded for St. Elizabeth’s Episcopal Church in Roanoke, Va., and also for Leaksville United Church of Christ in Page County, Va. Lectionary: Matthew 27.1-54.

Background on icon from Henri J.M. Nouwen’s Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons, which was a reading in Dr. William Roberts’ icons class at Virginia Theological Seminary, fall 2019. Contemplative prayer sessions were created by Andrew Lazo, M.Div. ’22.